Dot dot dash: 35 years that shrunk the world

Posted: September 23, 2024

The history of telecommunications

The year is 1860. Summertime. A lone horseman is thundering across the plains of Wyoming, carrying no food, no water – just a saddlebag full of letters. He is 14 years old and almost delirious with exhaustion. By the time he stops, he will have ridden without sleep for 22 hours. The young rider’s name is Buffalo Bill, and he is a diligent employee of the recently opened Pony Express, a network of stations, horses and riders that connects the gold-rich outpost of California with the more established states of the American Mid-West. In 1860, the Pony Express is quite possibly the most lightweight and rapid mail service ever devised. It is a triumph of logistics that has cut communication time between the Pacific coast and Missouri to a mere 10 days.

Yet within 18 months, the Pony Express will be utterly outmoded, its daring, manic riders characters from a romanticized past. Nothing will be able to compete with the reliability, accuracy and electric speed of the telegraph. In October 1861, across the very same plains on which Buffalo Bill made his name, the final gap in the transcontinental telegraph line closed, and communication between California and the rest of the United States became practically instantaneous. Just five years later, an underwater telegraph line would connect North America to Europe, transmitting information from London to San Francisco in hours.

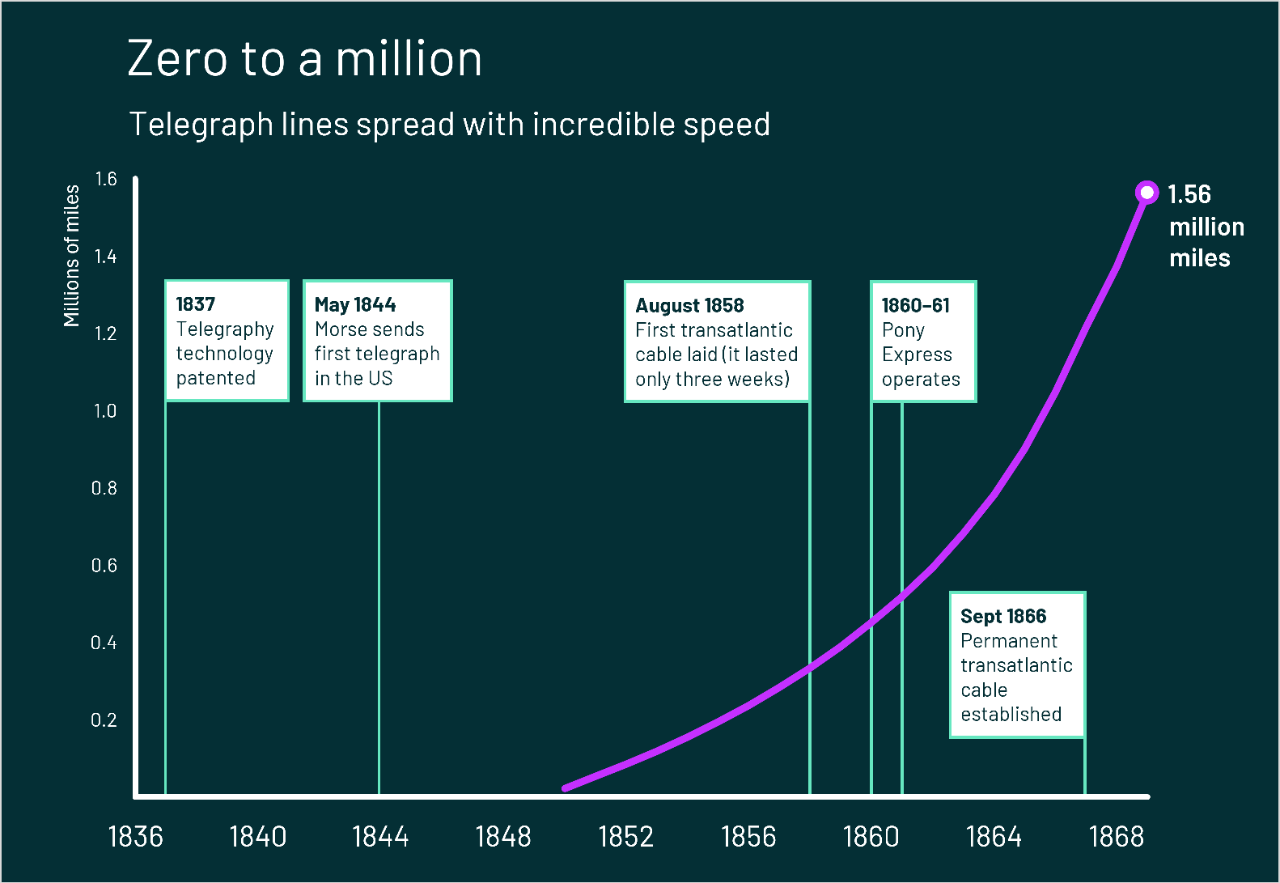

We talk a lot about the current pace of change and the acceleration of technological innovation, but you could argue that the 21st century has nothing to rival the explosive growth of the telegraph line, which went from a speculative scientific theory to a vast global network in just 30 years.

Our Industrial Life

Get your bi-weekly newsletter sharing fresh perspectives on complicated issues, new technology, and open questions shaping our industrial world.

How the telegraph industry began

In truth, the Pony Express was always an anachronism. By the time it was established, telegraph technology had been under patent for over 20 years, and the telegraph business was thriving. English inventors William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone were developing the industry in Europe, while a syndicate led by one Samuel Morse dominated the U.S. market.

The 41-year-old Morse – a portrait painter by trade – was an unlikely figurehead for the American telegraph industry, but he had an acute understanding of the emotional stakes of rapid remote communication. In February 1825, ten years before his invention of the telegraph, Morse was working in Washington, D.C. Missing his wife in Connecticut, he penned her a letter in which he lamented, “I long to hear from you.” She had died suddenly of a heart attack three days earlier. Washington was a four-day journey from New Haven, meaning Morse only received news of his wife’s death by post the following day—too late to get home in time for her funeral.

Data compiled and interpolated from contemporary sources.

Twelve years later, while creating his new telegraph system, Morse and his assistant devised a clever method for encoding written text, an approach that would lay the groundwork for encoding information in computers. A series of dots and dashes represented each letter of the English alphabet: a code that made it relatively easy to send complex messages across the wire. Coupled with the lever-key machine he invented to generate the signals, Morse’s code would become the global standard. In May 1844, Morse put all of his innovations together to send four words from the chamber of the Supreme Court in Washington D.C. to the Mount Clare railway station in Baltimore. “What hath God wrought?” Morse wondered into the electric ether.

The growth of the telegraph system

People, meanwhile, wrought telegraph lines. By 1856, European lines connected Moscow, Naples, Madrid, Amsterdam, Paris and London with thousands of smaller towns. In North America, lines went as far south as New Orleans, as far north as Nova Scotia, and as far west as St. Louis.

The most impressive telegraph project of the era, however, was undoubtedly the mission to lay the first telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean. After several failed and ruinously expensive attempts, in August of 1858, two converted warships, the USS Niagara and the HMS Agamemnon, successfully connected Valentina Bay in Ireland to Newfoundland in Canada. Soon after, Queen Victoria sent an inaugural message to President James Buchanan across the submarine wire. Her 98-word message took roughly 16 hours to travel from London to Washington – that’s a rate of nearly 10 minutes per word (or six words per hour). Some hours later, the President’s response came through:

“May the Atlantic telegraph, under the blessing of Heaven, prove to be a bond of perpetual peace and friendship between the kindred nations, and an instrument destined by Divine Providence to diffuse religion, civilization, liberty, and law throughout the world. It is a triumph more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle.”

Map of European telegraph network in 1856. [1]

Ten minutes per word may seem a comically snail-like speed of transmission today. But to the people of 1858, these transatlantic communications appeared both flabbergasting and magnificent. A great cable jubilee soon followed, complete with commemorative souvenirs made from small sections of unused original cable that were stamped and sold by the luxury jeweler Tiffany & Co. Festivities erupted in cities across the United States, Canada, and Great Britain. In New York, a day of celebration ended with City Hall nearly burning down after it caught fire from the fireworks.

One American newspaper proclaimed:

“New York has seldom seen a more complete holiday than that…in celebration of the successful laying of the Atlantic cable. The enthusiasm of an entire nation was expressed in this jubilee … The streets were profusely decorated with flags of every nation, festooned upon the stores and houses, or drawn across the street … At night the illuminations, fireworks, torch-light processions, etc., etc., were on a scale of magnificence heretofore unequaled.”[2]

The New York Herald wrote[3]:

“It was exceedingly beautiful, and as the long line moved through Broadway surrounded by an enthusiastic crowd on every side, and lighted by thousands of torches, candles, and colored lanterns, one might easily have imagined himself in a fairyland. … but we do not lay Atlantic cables every day.”

For the first time in history, humanity was presented with the possibility of communicating across oceans in a matter of minutes. To people of the time, the world appeared to be shrinking before their very eyes, and yet seemed more full of hope and promise than ever before.

One historian at the time wrote[4]:

“The laying of the telegraph cable is regarded, and most justly, as the greatest event in the present century,” […] “Now the great work is complete, the whole earth will be belted with electric current, palpitating with human thoughts and emotions. It shows that nothing is impossible to man.”

The 1858 cable eventually failed and was replaced by a new cable in 1866, creating a more permanent link between Ireland and Newfoundland. With a transmission rate of eight words per minute, the new cable was a significant improvement over the old one. Its success marked the beginnings of what the writer Tom Standage later called in his 1998 book of the same title, The Victorian Internet. By 1870, Suez was communicating with Bombay via telegraph wires. From there, messages went on to Madras, Penang, and Singapore. Lines linked London to Bermuda and Barbados. In 1871, a line connected Singapore to Port Darwin, and by 1872 Queen Victoria could communicate directly with Sydney and Adelaide. Electrical wires crisscrossed continents and seas, roping the world with electrical messages in a truly global network.

In the winter of 1868, at a banquet held in honor Samuel Morse’s accomplishments, one particularly effusive partygoer rose to give a toast. Morse, he said, had:

“annihilated both space and time in the transmission of intelligence. The breadth of the Atlantic, with all its waves, is as nothing.”[5]

Yet, like Buffalo Bill and the Pony Express before him, Morse and his innovations were already slip-sliding into obsolescence. In the 1870s, a new device was emerging that could transmit something far superior to a cryptic sequence of dots and dashes. Astonishingly, this new technology used existing telegraph lines to transport the exact timbre and personality of the human voice. The age of the telephone had arrived.

References

[1] “The Electric & International Telegraph Company's map of the telegraph lines of Europe” Published under the Authority of the Electric Telegraph Company by Day & Son, Lithographers to the Queen. August 1, 1856.

[2] The Iconography of Manhattan Island. Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, 1915. Page 61.

[3] Cyrus W. Field, His life and work [1819-1892]. Isabella Field Johnson. New York Brothers Publishers, 1896. Page 117.

[4] The story of the telegraph and a history of the great Atlantic cable. Charles F. Briggs and Augustus Maverick. Rudd & Carleton, 1858. Pages 11-12.

[5] The Victorian internet. Tom Standage. Bloomsbury, 1998. Page 90.