How the Romans built the aqueducts

Posted: January 17, 2025

Roman author and philosopher Pliny the Elder was among the first of many to wax poetic about the Roman aqueducts when, in the first century AD, he wrote:

“If we only take into consideration the abundant supply of water to the public for baths, ponds, canals, household purposes, gardens, places in the suburbs, and country houses; and then reflect upon the distances that are traversed, the arches that have been constructed, the mountains that have been pierced, the valleys that have been leveled, we must of necessity admit that there is nothing to be found more worthy of our admiration throughout the whole universe."

The ancient Romans would build only about a dozen aqueducts to supply their capital city over the span of roughly 500 years, starting with the Aqua Appia in 312 BC.[1] But they would also export its design to the farthest reaches of the empire, cementing the aqueducts as the most enduring example of Roman civil engineering.

Our Industrial Life

Get your bi-weekly newsletter sharing fresh perspectives on complicated issues, new technology, and open questions shaping our industrial world.

Today, the soaring arches of the Pont du Gard in France, the Tarragona Aqueduct in Spain, the Caesarea Aqueduct in Israel and the Zaghouan Aqueduct in Tunisia are a testament not only to the reach of the Roman Empire but to its enduring methods of construction.

They’re also slightly misleading: the vast majority of Roman aqueducts were not made up of soaring arches and arcades, but rather simple covered tunnels or trenches dug into the ground.

Covered tunnels and soaring arches: the making of the aqueducts

Regardless of their style, all aqueducts required careful planning and minute execution. Roman engineers needed to make sure the water would traverse great distances while dodging the threat of evaporation and sabotage; cross valleys and mountains; and maintain the right flow speed throughout.

The aqueducts all relied on the force of gravity to move water, which meant getting the gradient right was key. Making an aqueduct’s slope too steep would mean the water pressure could burst through pipes and retaining walls or empty a reservoir too quickly.

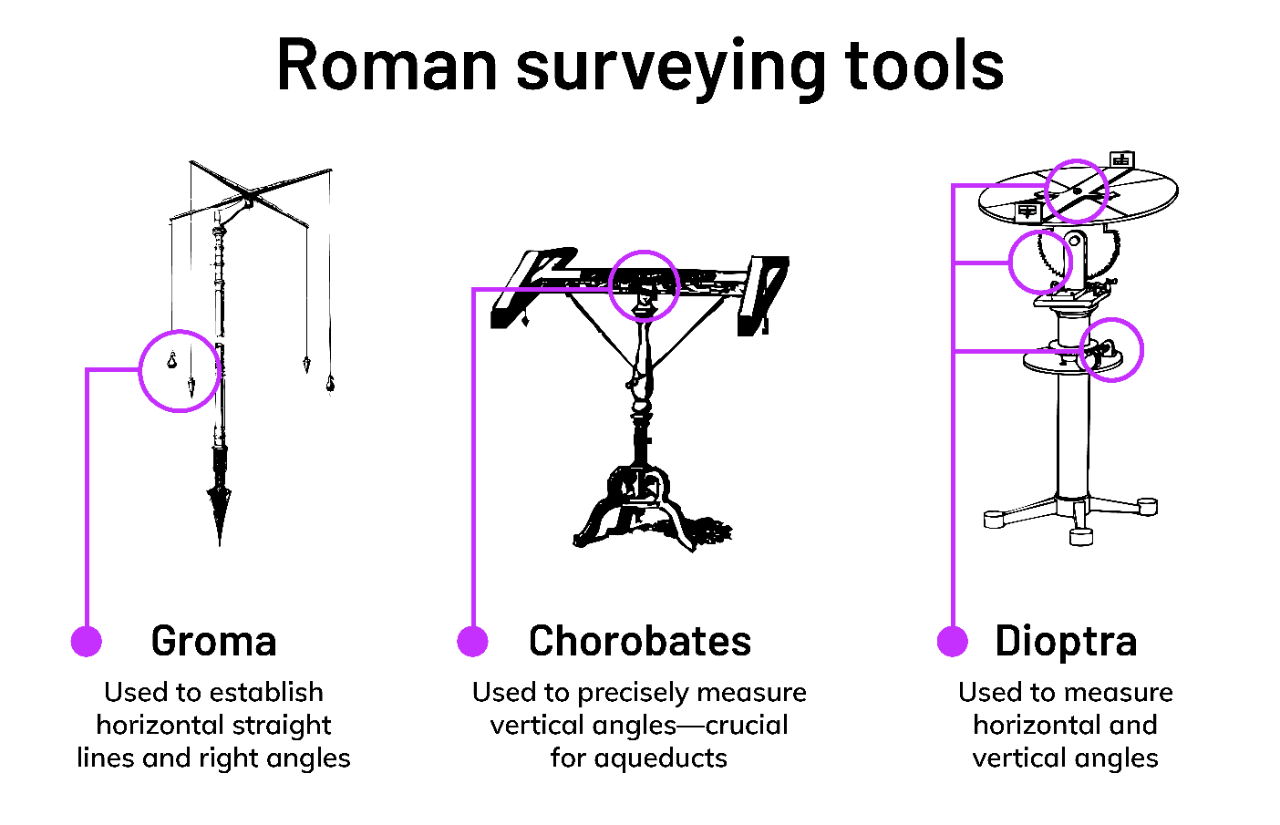

To get a lay of the land and plot their aqueducts, Roman engineers throughout the centuries relied on three simple surveying instruments: the groma, dioptra and chorobates.[2]

The groma, used as far back as the ancient Greeks to sight straight lines and right angles, consisted of a pole with a cross mounted at the top and a plumb line attached to each of its four points. The dioptra was a column of gears and rotating plate screws used for leveling and measuring angles.

The chorobates, hailed by Roman architect Vitruvius in the first century BC as the most reliable of the instruments, was essentially a 20-foot table with plumb lines and a water level that surveyors would set up directly on the floor of the water channels cut by their workmen.

Using these basic tools, Rome’s surveyors eventually channeled through mountains and spanned valleys with bridges, viaducts and siphons to supply water to dozens of cities throughout the provinces.[3]

Back in the capital, the purpose of the aqueducts wasn’t always purely existential. Although most Romans likely drew household water from them, one of their primary functions was to fuel the Romans’ passion for bathing.

At the height of the Roman Empire, the capital was home to close to 1,000 public baths, many of them lavish marble complexes and all of them fed by a sprawling system of aqueducts, cisterns and reservoirs.

Built to last: Roman engineering and construction

By the time Pliny was writing so gushingly about the capital city’s water works in the first century AD, Rome’s early aqueducts had already gone through a cycle of neglect and renewal. The rise of Rome’s first emperor Augustus in 27 BC had ushered in a new period of refurbishment and construction. The consul and architect he put in charge of the project, Marcus Agrippa (coincidentally also Augustus’ son-in-law), erected new raised canals and sprinkled the city with ornamental fountains.

Still, perhaps in a sign of the empire's broader decline, later aqueducts showed signs of less substantial construction and cruder repairs. The last of ancient Rome's 11 aqueducts, the Aqua Alexandrina, was finished in 226, roughly a century before the central government moved to Constantinople and 250 years before the collapse of the Western Empire.

The sturdy workmanship of the Pont du Gard in France (left), the Zaghouan aqueduct in Tunisia (top) and the Pont del Diable in Spain (bottom).

The sturdy workmanship of the Pont du Gard in France (left), the Zaghouan aqueduct in Tunisia (top) and the Pont del Diable in Spain (bottom).

One of the reasons so many of them remain standing today is the choice of materials: the Romans used a mix of stone, terracotta, brick, lime mortar, cement and later even concrete, sometimes enhanced with volcanic ash. Lead pipes were commonly used in aqueducts, too. (The hard, mineral-rich spring water had the beneficial side effect of insulating the pipes with sediment to reduce contact with the lead over time, even if it also required regular clearing.)

Rome’s hydraulic engineering was actually in evidence long before the aqueducts. The Cloaca Maxima, originally an open-air drainage channel designed to keep the lower sections of the city dry, became the foundation of Rome’s sewer system several hundred years before the first aqueduct was built.

In fact, modern water supply systems to rival those of ancient Rome were not built until the nineteenth century. Even today the Aqua Virgo, constructed in 19 BC during Augustus’ reign, still supplies water to Rome’s famous Trevi Fountain.

No wonder Edward Gibbon, in his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, counted the aqueducts as “among the noblest monuments of Roman genius and power.”