The precarious uranium supply chain—visualized

Posted: February 25, 2025

Nuclear energy is having a moment.

According to the World Nuclear Association, about 65 large-scale reactors are under construction across the world, with another 90 planned. The first small modular reactors (SMRs) are already in operation in China and Russia, and the IEA projects that there could be 1,000 SMRs in operation across the world by 2050 given sufficient investment.[1] All in all, the IEA estimates that by the middle of the century, nuclear energy capacity will be 50% greater than it is today.[2]

But this growth in output relies on one not-so-secret ingredient: uranium. It’s impossible to fully appreciate nuclear energy’s much-discussed renaissance without some knowledge of this indispensable, radioactive heavy metal.

So here, in four simple graphics, is how uranium goes from the Earth’s crust to nuclear fuel.

Our Industrial Life

Get your bi-weekly newsletter sharing fresh perspectives on complicated issues, new technology, and open questions shaping our industrial world.

Global uranium reserves: where is uranium found?

In trace amounts, uranium is present in all rocks and soil, as well as in the air—researchers have even started exploring the possibility of extracting it from seawater. Commercially viable deposits of uranium, however, are highly concentrated in just a few nations.

Australia has 28% of global reserves all by itself. Yet despite its world-leading reserves and established mining industry, Australia’s relationship with uranium mining has long been a hot political topic—in fact, the very size of its deposits has contributed to the country’s hostile attitude towards the resource.

During the Cold War, many Australians felt the country’s uranium output was contributing to the threat of nuclear war. In the late 1970s, the Australian Labour Party vowed to cease uranium mining. That never came to pass, but hostility to uranium extraction has endured, in part due to the potential harm that the radon released in mining operations can have on workers and the local environment.

Top uranium-producing countries

Australia’s attitude towards uranium means that it is not the world’s leading producer. That title belongs to Kazakhstan, which is responsible for a whopping 43% of global output.

Kazakhstan has an even more fraught history than Australia with nuclear technology—it was the testing ground for Soviet atomic weaponry, with devastating consequences to the local people—but last year nonetheless voted in favor of developing its own nuclear energy infrastructure.

The country’s nuclear ambitions and existing uranium mining operations are entwined with Russia. “Russian state nuclear firm Rosatom, which has previously been Kazakhstan’s default partner for nuclear projects, still controls a large share of Kazakhstan’s uranium reserves,” write Jennet Charyyeva and Yanliang Pan in a recent piece for the Carnegie Endowment.

Because uranium is soluble, most mining is done through a process called in-situ leaching (ISL). The process involves pumping a liquid solution underground, into which uranium dissolves. The solution is then pumped back up to the surface, where the uranium is extracted from it. According to the World Nuclear Association, Kazakhstan is “by far the world leader in using ISL methods.”

After being filtered out of the solution, uranium oxide is dried into a powder called “yellowcake.”

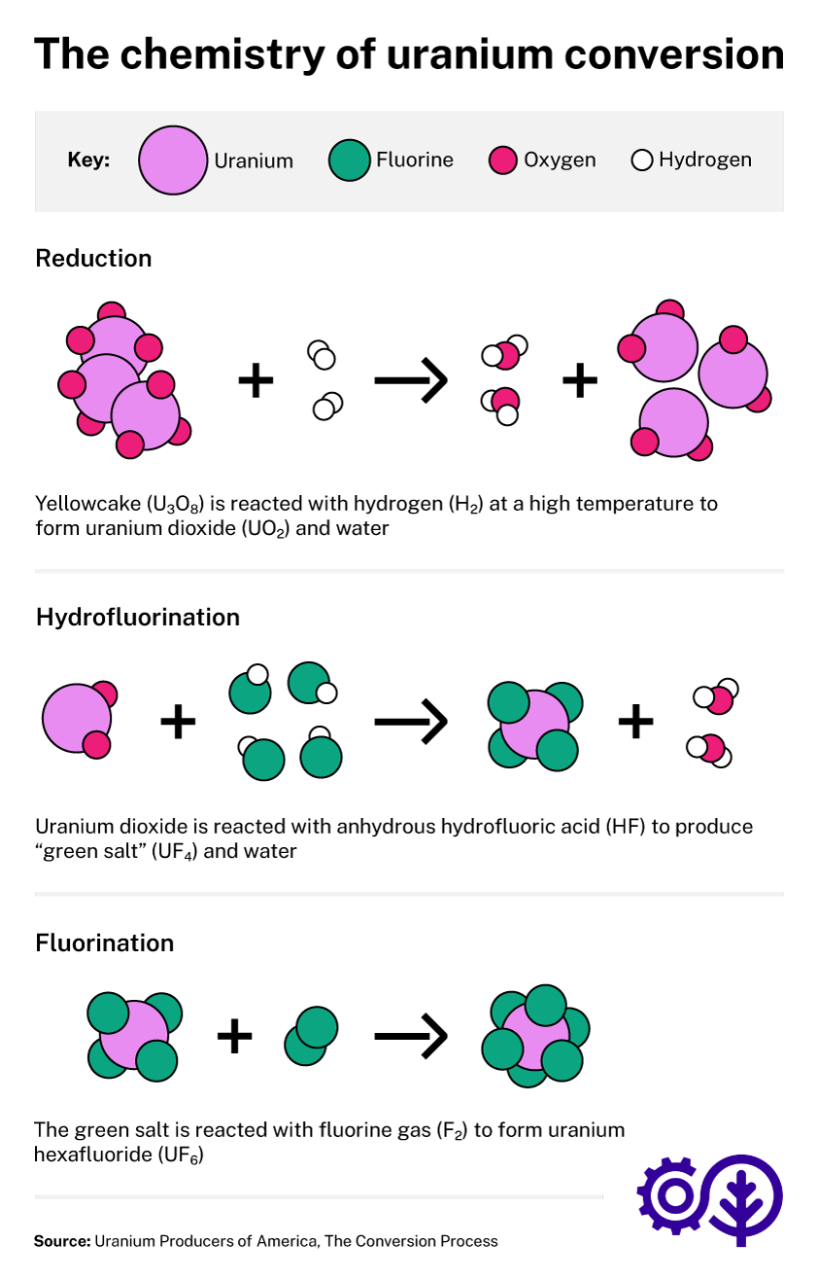

Uranium conversion: the first step in nuclear fuel processing

With the notable exception of the Canadian CANDU model, most nuclear reactors require yellowcake to be enriched before it can be used as fuel. The first stage of the enrichment process is the conversion of yellowcake into the gas uranium hexafluoride.

Conversion is perhaps the most concentrated stage in the nuclear energy supply chain: there are just five conversion plants in operation today, located in Canada, China, the United States, France and Russia.[3]

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Uranium enrichment: how nuclear fuel is made reactor-ready

In both yellowcake and uranium hexafluoride, there are two different uranium isotopes: U-235 and U-238.[4] The latter isotope is far more common, but nuclear reactors produce energy by splitting the U-235 isotope.

“Enrichment” therefore refers to the process of stripping away some of the U-238 isotopes, so that the concentration of U-235 isotopes reaches a high enough level.

This is achieved with fast-spinning centrifuges in which the slightly heavier U-238 isotopes are flung out to the edge of the chamber, while the lighter U-235 isotopes collect in the middle.

In nuclear reactors, the percentage of U-235 is typically between 3–5%; in nuclear weapons, it can be as high as 85%.

Although there are many more enrichment facilities than conversion facilities dotted around the world, the IEA estimates that over 99% of enrichment capacity is held by just four companies: China National Nuclear Corporation (15%), Russia’s Rosatom (40%), Urenco (a British-German-Dutch consortium, 33%) and France’s Orano (12%).[5]

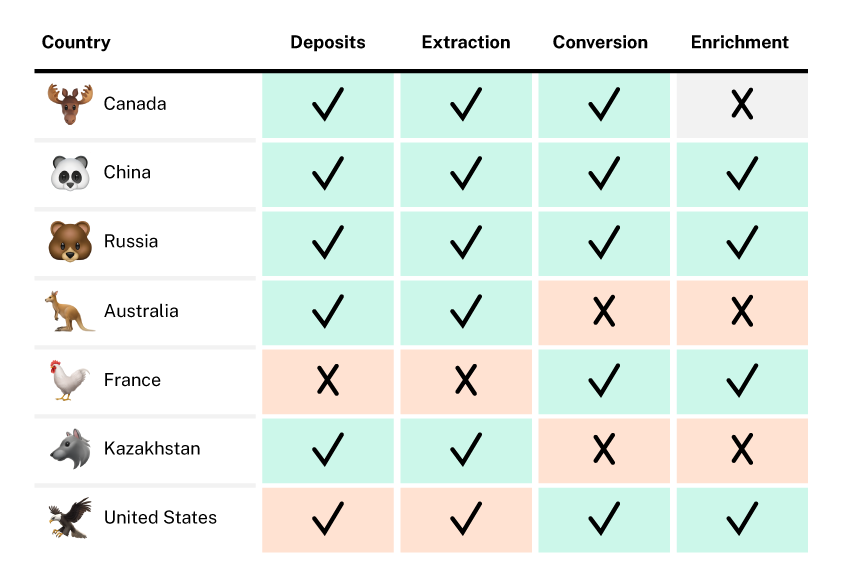

The uranium supply chain scorecard

A simplified rendering of the uranium supply chain highlights that only Canada, Russia and China have the combination of natural resources and technological know-how to be self-sufficient producers of significant quantities of nuclear energy.[6]

It is unlikely coincidental that China and Russia are investing heavily in their nuclear energy capacity. China, especially, is significantly expanding its nuclear fleet—half of all nuclear power plants currently under construction are located in the country.[7]

In spite of the renewed global interest in nuclear energy, and notwithstanding the IEA’s projection of a 50% rise in output, the global production of uranium is not forecast to rise in line with demand. It hasn’t need to—for a while now, the shortfall in production has been plugged by the secondary supply of uranium found in strategic reserves and weapons stockpiles. Such drawdowns can’t go on forever, of course, but given it can take 15 years for a deposit discovery to turn into an operational mine,[8] the stockpiles will be critical for decades to come.

Which is to say that if the constrained supply chains of uranium are keeping you up at night, you’d do well to follow the lead of a certain Dr Strangelove.

[1] The Path to a New Era for Nuclear Energy International Energy Agency, p. 58.

[2] ibid., p. 43.

[3] ibid., pp. 64-65.

[4] They also include 0.01% of the U-234 isotope.

[5] The Path to a New Era for Nuclear Energy International Energy Agency, p. 65.

[6] Canada’s CANDU reactors, which do not require enriched uranium, make the country potentially self-sufficient even without enrichment facilities. The U.S. does produce its own uranium, but in very small quantities relative to its energy demands.

[7] The Path to a New Era for Nuclear Energy International Energy Agency, p. 14.

[8] ibid., p. 64.