What can you do with wind turbine waste?

Posted: September 09, 2024

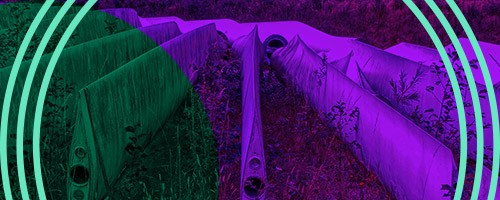

How do you dispose of a nearly-indestructible fiberglass structure half-a-football-field long? That’s the question engineers and urban planners are wrestling with now that the first generation of renewable-power wind turbines are coming to the end of their 20 to 25-year lifespans.

Fortunately, approximately 90% of a wind turbine’s mass is made from easily recyclable materials, such as steel, cement and copper, which make up the tower and mechanical components of the turbine. But the turbine blades themselves are made out of fiberglass or carbon fibers embedded in resin epoxy. The material is so durable, it’s difficult to mechanically cut into pieces or to chemically separate the fibers from the resin. So, right now, most turbine blades—each about 50 m long—wind up buried whole in landfills.

Our Industrial Life

Get your bi-weekly newsletter sharing fresh perspectives on complicated issues, new technology, and open questions shaping our industrial world.

By 2050, the U.S. alone will have accumulated something like 2.2M tons of wind-turbine blades to dispose of. They would occupy about 1% of its total remaining landfill volume. The rest of the world might well have over 45M tons by that time. So, companies and governments need some way to either repurpose old turbine blades or to deconstruct and recycle their components.

Re-using wind turbine blades

Several creative projects leave the blades largely intact and repurpose them as new structures, such as colorful park benches and playground equipment. The Re-Wind network of academics made a pedestrian bridge in Ireland, and has proposed building cell phone towers and fencing too.

But, ultimately, we’ll have more used turbine blades than we’ll have need for new outdoor furniture. So, we still need some way to recycle the blades as raw materials.

How can wind turbine blades be recycled?

Veolia, the water, waste and energy services company, uses special machines to grind up old turbine blades into small pebble-sized pieces, which it sells as alternative fuel for cement kilns. The resulting ashes can also partially replace limestone as an ingredient in the cement itself. Veolia estimates that cement made with repurposed turbine blades reduces CO2 emissions by 27%.

Another project, run by the Carbon Rivers company and funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), uses high temperatures in a process called pyrolysis, which breaks down the blades’ epoxy into syngas and pyrolysis oil. Both products work as alternative fuels, and the oil can serve as a precursor for manufacturing new polymers. The process leaves behind fiberglass that’s clean of epoxy, ready to recombine with new epoxy to form new materials.

In partnership with CETEC, an industrial-academic coalition devoted to finding solutions to recycle wind turbine blades, the wind turbine company, Vestas, has developed a chemical process that can separate the turbine blades’ fiberglass from epoxy. The chemical process then further breaks down the epoxy into “virgin-grade materials” that could potentially be reused to construct new wind turbines. The company says that the process relies on widely-available, non-toxic chemicals and promises to consume little energy and produce few CO2 emissions. Vestas still needs to scale the process up to work at an industrial scale and has so far been keeping the details under wraps.

Can wind turbine blades be re-engineered?

Because it’s so difficult to break down the epoxies that make up the current generation of turbine blades, several companies are developing materials that are easier to recycle.

Researchers at Michigan State University made a new turbine material by combining fiberglass with a resin that’s composed of two polymers, one plant-derived and the other synthetic. While it’s sturdy enough to construct turbine blades, the new resin easily dissolves in a chemical solution, allowing the glass fibers to be retrieved and the resin to be recast into new shapes while maintaining all its physical properties.

The resin can also be digested in other chemical solutions to create acrylic material for car windows, absorbent polymers for diapers, and even…gummy bears.

“We recovered food-grade potassium lactate and used it to make gummy bear candies, which I ate,” researcher John Dorgan said.

As for making turbine blades out of the new resin, “the current limitation is that there’s not enough of the bioplastic that we’re using to satisfy this market, so there needs to be considerable production volume brought online if we’re going to actually start making wind turbines out of these materials,” Dorgan says.

Meanwhile, Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy SA has already constructed and installed turbine blades with a new resin it developed that dissolves in a heated acidic solution so that it can be recycled.

What is the future of wind power?

The solutions above are just the beginnings of concerted efforts to make wind power generation as sustainable as possible. The U.S. Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is funding a wind turbine recycling prize, with 20 winning teams in the U.S. thus far receiving stipends to develop new technological proposals further.

As we wait for all these innovations to advance, it’s important to remember that wind power generation produces far less waste than many other industrial activities—and it’s non-toxic. Assuming that turbine waste in the U.S. grows as projected to 370,000 tons per year by 2050, it would only constitute .15% of the annual solid and construction waste the U.S. generated in 2018. So, even with current technologies, wind power remains one of the most sustainable means of power generation.